FLAWED GENIUS-26

Driven To Create

Chapter 26 (first draft)

Slot Car Racing

Having a relationship with Kim was like playing volleyball with a tall pine tree as the net. Dad was the tree. My stepmother was a sexy, sensual woman. Undoubtedly, what drew him to her. His standard line, shared with me in the familial intimacy of his ‘57 Corvette on the way to Evansville, was “We’d been married for eight years, and I had just fallen in love with your mother when she left me. Adding insult to injury, she took my trombone player with her.” Usually, he would pause before adding, “And to boot, after she left, I had difficulty performing.” I thought I knew what he meant, but I didn’t.

In grade school, girls were sweet, annoying, mysterious, and baffling. We guys knew something was supposed to happen with them eventually, but no one would admit to having solid information. Rumors, suppositions, and juvenile theories filled our heads. When Dad talked about having trouble performing, I nodded, holding my breath in fear he would add details. He never did. Kim became an enigma to me, an unapproachable feminine mystique.

Our new home had three camps: Dad and me, Jan, Kim and Chris. I loved my sister, but could not ally with her against Dad. Whenever Kim and I found ourselves alone, I would freeze up, worried I would say something that would make me appear to be on her side about an issue. Any issue. I can only guess how Chris felt about Dad. She was as much in her mother’s camp as I was in Dad’s. Jan’s unhappiness was deep-seated. It erupted often, pushing her into an orbit of one.

*****

Dad continued to sell kart parts out of a storage section of his old shop. His supply was dwindling. One day, he brought my kart home and put it into the outdoor storage, a closet on the back of what had been the garage with only outside access. “The karting business is about dead, Bob. I invested $50,000 and lost $60,000.”

“I kind of guessed that, Dad. How come you brought my kart home?”

“Well, it’s your kart. You can sell it if you want to.”

“Can I race it?” I didn’t really want to, but thought I should say something like that for Dad.

“You could, Son. But I doubt it would be competitive anymore.”

I sold it the following year for $600 to a guy Dad found from Southern Illinois who was jazzed to race my old kart. Dad told me later that it performed well, but the man who bought it did not know how to set it up and was an average driver. I used some of the money to buy a five speed Western Auto bicycle.

*****

Dad named his new stamp business “The Cowling Company” by having letterhead printed. With three decades of casual collecting behind him and a deep passion for the hobby, he began buying inventory. And buying and buying. US, foreign, mint, and used stamps, in singles, blocks, and sheets. The stamps of San Marino, a mountainous microstate in north-central Italy, were his favorite. He liked their designs and appreciation. A year later, the market crashed. The philatelic world had gone through an unprecedented surge in value. Conservative dealers had warned Dad it was a bubble. He did not listen. Sadly, it gradually became clear to him that he had bought at or near the peak. Out of capital, Dad tucked away his inventory in file boxes, stored them in the cabinets under the window of our family room that looked out on the driveway, and waited for the market to recover.

*****

We went to Purple Aces games as a family at first. When Jan, Chris, and finally Kim lost interest, only Dad and I went. The team electrified Evansville by winning the Small College National Championship back to back in ‘63-’64 and ‘64-’65. Jerry Sloan and Larry Humes were standouts. Dad said good basketball players had a common trait: they looked like birds of prey. Jerry Sloan fit that profile, not sure about Larry Humes.

Dad also said it was tough to beat a good team three times in one season. Evansville defeated Southern Illinois twice, home and away, during the regular ‘64-’65 season. Both games went down to the wire. Walt Frazier led the Salukis, Jerry Sloan the Aces. The 1965 championship game pitted these rivals against each other. The tournament was played at Roberts Stadium. Dad said homecourt should give the Aces the advantage. Since we had won both previous games, though, the Salukis would have the momentum for the third one. In my mind, I was beginning to question Dad about how he treated people, but not about basketball. He had years of experience on me. We yelled ourselves hoarse at the championship game, watching as the Purple Aces won in overtime to complete a perfect 29-0 season, winning the National Championship for the fourth time in seven years. That it was the small college, not the university division championship, and it was played on the Aces’ home court, mattered not to us or anyone in attendance. We figured Jerry Sloan was all-world, and Larry Humes not far behind him.

*****

I was fourteen when we moved to the Tremont house. Jan and I started at North High, a large school for us. I knew no one. Ironically, a handful of my school buddies became good friends after we graduated. I bumped along my freshman year by myself. Home life had the same feel. Dad was busy with his stamps, Jan was struggling, and I shied away from Kim and Chris. My body and mind were changing, and I had no one to talk to about it.

My room was the smallest in the house, which made sense to me because I was the only one with a room to myself. Dad put the daybed in it for me to sleep on, plus a small chest, bulky desk, and chair. The 9’ x 9’ room was full. Tucked in behind the furnace room with a three foot entryway to our main hallway and the bathroom, I felt secure and isolated. Dad helped me mount three long shelves above my bed. The first two rows were 2 x 10s. The top one was a 2 x 8. All painted black and loaded with trophies.

Sleeping in this small, packed room under a wall of my racing awards cocooned me. That fall, I began wondering about myself, Dad, and the world. Growing uneasy with how my father interacted with people and feeling unable to share my feelings, the idea of changing him felt preposterous.

Night after night, I lay in bed half asleep, posing questions to the universe. Gradually, words fell away from my thoughts. Concepts began to filter in from...I don’t know where. Today I would say I was opening to the inner, nonphysical, spiritual worlds. I have studied a spiritual path for the past forty years, so I have a foundation. At fourteen, I had nothing to anchor my thoughts. But I collected them over the course of months during these midnight meditations. By spring, I knew who I was. Had no words for it, but I knew...and I wasn’t going to be like Dad.

*****

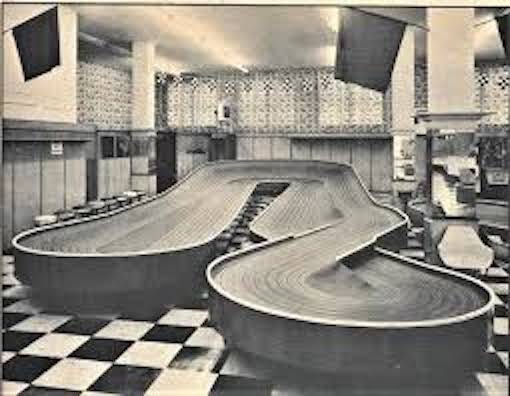

ABOVE: 1960s slot car track

BELOW: Purpose-built slot car track, similar to the ABC Hobbycraft track in 1965. The over and under configuration equalized the lanes.

That summer, Dad and I got into slot car racing. He had haunted model shops all his life, whether planning or building a train layout. As a boy, he built model airplanes from scratch. I often went with him to ABC Hobbycraft. Ken Ballard was the long-time owner, in a career that lasted twenty-five more years. Dad carried a subtle arrogance that I picked up and mirrored. I knew I was not as experienced or talented as Dad, but he voiced his opinions often enough that I took them to heart. Bottom line: Dad thought he was smarter and more talented than most people. Those people he considered equal or above him, he put on pedestals, heaping exaggerated praise on them. His attitude may have helped him overcome his insecurities. Overall, though, it created a personal relationship headwind.

He bought me Mattel HO race car sets early in my childhood. I loved them and would play for hours, setting up tracks and holding races between cars. The original controllers were small steering wheels mounted on facsimile dashboards. A pin in the front of the car kept it in its lane. The steering wheel controlled the power and would stay set at any speed. I adjusted each car to drive as fast as possible without coming off the track throughout a lap. Watching two “drivers” zip throughout a complicated track side by side, passing and being passed as a right hand turn switched back to a left hand one, was thrilling to my seven-year-old self. I watched these races, built and rebuilt tracks, and changed out cars for hours at a time, totally enthralled.

Track designing became a hidden passion. In my early twenties, I designed my RACE board game. Based on the odds inherent in rolling dice, I incorporated attrition and speed factors into a four car race over a road course layout on a folded game board.

The same passion led me, as an adult, to be the lead organizer of an activity based, family nonprofit organization for twenty years in Honolulu. We built tracks and box cars, taught kids and parents how to build their own box cars, held races, and hosted birthday parties. The latter rocketed participation levels from 350 people in our third year to 40,000 in our fifth year.

In 1965, Dad and I began racing slot cars on the new eight-lane track at ABC Hobbycraft. I assembled the frames and drove. Dad sourced modified motors from California and built beautiful model racing car bodies. We won a bunch more trophies over the next year and a half. It was a good father-son activity, though layered with our individual limitations.

The dream in those days was to steer the model cars as they raced. Take the slot out of slot cars. Forty-five years later, our nonprofit group built paved road courses for RC cars next to our box car tracks at our “permanent” track in the Kunia neighborhood of Oahu. Driving a slot car was all throttle and brakes, which happened automatically when the throttle was released. I mastered this as a teenager at ABC’s seventy foot track.

Driving a model car around a five hundred foot long track with banked turns and multiple switchbacks at age sixty was a whole other ball game. The cars topped out at 300 scale mph. Controlling them was not intuitive. Standing on a raised driver’s stand, trying to see the track from the perspective of an imaginary speed demon changing directions several times a lap, racing a hundred feet away, using a controller for both steering and speed was hard. Beyond my abilities.

I got to build tracks, run races, schedule parties, check in families, and a thousand other things at the Box Car Track in Kunia, which morphed into Race World Hawaii. Our activities quickly outpaced a volunteer staff. Program fees allowed us to hire teenagers to help run things.

Managing a revolving staff of a dozen part-time, hormone compromised young people was one of the top ten most difficult things I have done in my life–and very rewarding. I made weekly runs to Sam’s Club to buy snacks to sell to families who came to drive during open track instead of attending a birthday party. Staff could munch free on the chips, sodas, cookies, and water. Gradually, I realized these snacks were the teens’ meals. Horrified by the poor nutrition being consumed, I eliminated the snacks and bought lunches for them.

Getting teenagers to show up on time was a challenge. Finally, I posted an online bit of wisdom that proved effective: “Being early is being on time; Being on time is being late; Being late is being a Bozo.”

ABOVE: Race World Hawaii before closing.

BELOW: 10 years after the City forced us to close the track.

#

To read my previous posts, sign up for a Substack account (if you haven’t already). It’s

free and only requires your email (no cc). Unsubscribe at any time with one click.

To learn about my other books, click the link below to my author’s website.https://bccowlingbooks.com/