FLAWED GENIUS-27

Driven To Create

Chapter 27 (first draft)

Andi

During my wild time with cousin Carol’s VW in the fall of ‘66, I began smoking. No particular reason, other than most adults around me did. I knew I had to hide it from Dad. He often said how stupid a habit smoking was, as he puffed away.

Tim and I considered each other brothers with different mothers…and fathers. His home life was consistent, mine erratic. I smoked for six years, Tim never started–and he was in a rock band. His innate common sense and involved parents steered him through a successful life and career. Many of my decisions were all over the map, often making life difficult.

After bashing up the VW, I was chagrinned at how much trouble I had caused. Two years after my midnight meditations, and still looking within, I sought more understanding. Meaningful guidance would come twenty years later. For my teens and twenties, however, I had no positive adult role model, only an untethered creative one.

Driving real cars made slot car racing seem trivial, but my friendships begun there grew stronger. Bruce, Steve, Ricky, and I became a foursome. Different guys, different families, but we meshed for a time. Bruce or I drove. We did what most young people did in Evansville: cruise the circuit from drive-in to drive-in. We would stop for Coke or a burger, ogling the car hops politely, or stay with the slow moving parade of guys showing off their rides or pecs. We had neither. Occasionally, when I drove, we’d hit a quiet neighborhood street in the evening. I would jam the Mustang’s shifter into reverse, burn rubber backwards, and slam it into first to do a long burn. Then I would drive like hell to get out of there quickly. Most of the time, we did not act like delinquents. The light ass end of the car made it burn rubber easily, like it had a 426 Hemi under the hood.

A byproduct of our slot car race days was getting to know each other and the parents. Dad, therefore, had no problem with me hanging out with these guys. I began to feel fractured. I behaved one way to please Dad and another when away from him. Going home felt increasingly like putting on a straitjacket.

I banged the rear fender of Dad’s Mustang that winter while out with the guys being silly. Dad yelled at me and paid to have the car fixed. Nothing else changed.

In the spring of ‘67, I fell in love. That fall, she dumped me. Said she needed someone more responsible. Later, I understood. At the time, it was hell. For the few months Andi and I were together, I experienced life like never before.

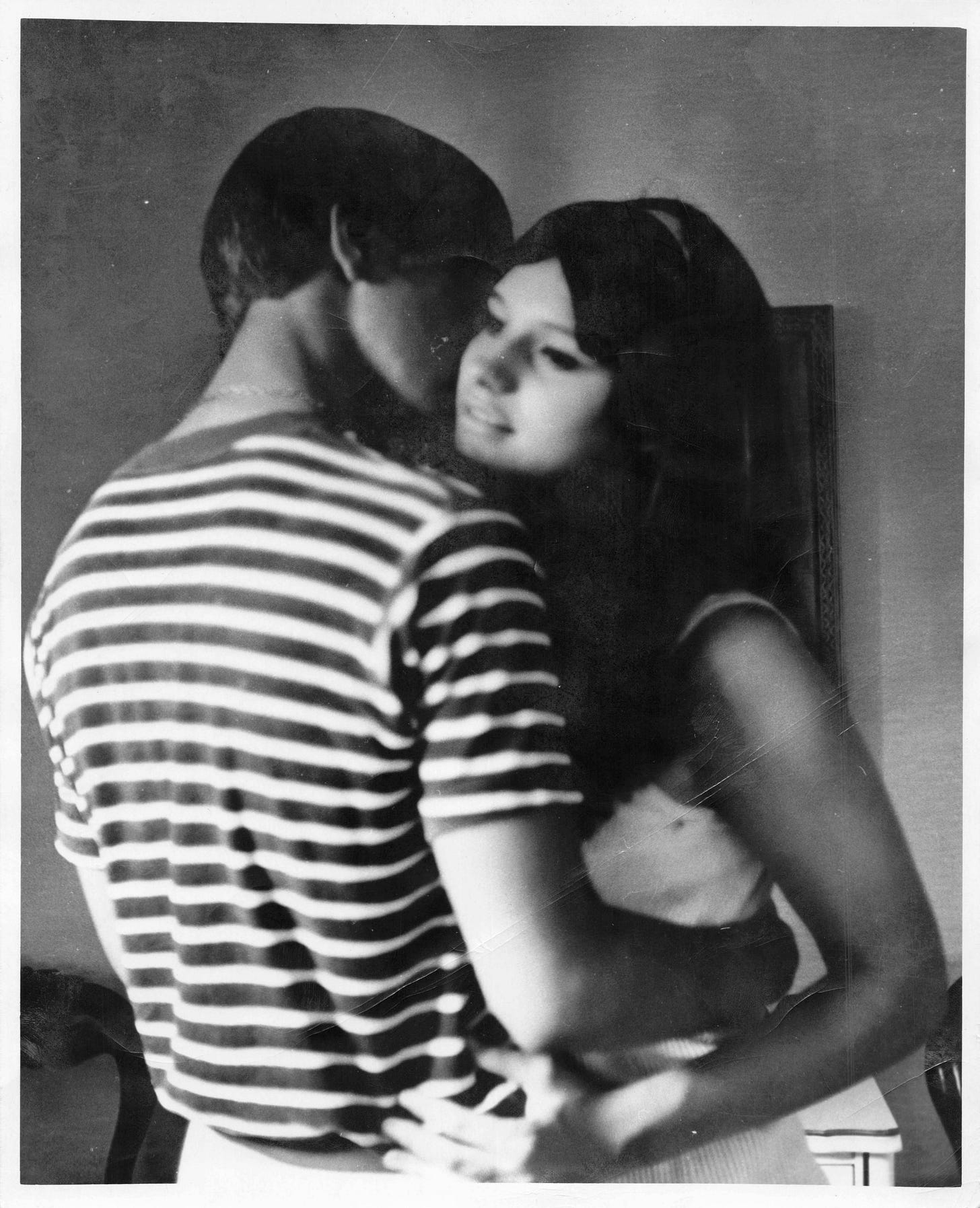

BELOW: Andi and I in the summer of ‘67.

I was still a boy, focused on the present. Long term plans were hazy. Andi was four months younger than I, but looked a decade ahead in her life. We went to movies, drove around, went out to eat with Dad, and hung out at my house. Not an everyday thing, which felt okay to me. I assumed it was what Andi wanted.

At seventeen, Andi was thinking about her future. She lived alone with her mother, who worked full time. Her father was long gone. Andi was vivacious, fun, and beautiful. Intellectually, she was at the forefront of the class, but not dedicated to her studies.

On the sly, we took a few trips to Mt. Carmel to see Tim and the Apollos play. Dad forbade me from driving out of town. He was concerned about racking up miles on the car. Or so he said. Maybe he was worried about me, about my judgment. Have no idea why.

Our last trip was in August. Left before the dance was over. No booze. At seventeen, alcohol was not a factor in our lives, nor Dad’s. I never saw him drink anything stronger than iced tea.

“Drank whiskey in my twenties until I did smack once,” he told me after I turned twenty-one and began drinking wine.

“What did doing heroin one time have to do with your drinking?”

“I thought I was blowing my horn great when I was high. Learned afterwards I sounded awful.”

“Okay. Sounds like a good reason not to get high. Why no more drinking, though?”

“My calculation. If heroin affected my playing that much, then alcohol must affect it too. No matter how little, I wanted nothing to affect my music.”

“That’s cool, Dad,” I said, but thought wine would not be a problem for me. By the time I hit thirty, alcohol had caused a problem in my life. A few years later, I experienced how altering my consciousness, even in a small way, greatly affected my meditation.

On the drive home with Andi that Saturday evening, she leaned against me. Cars in those days had neither seatbelts nor headrests. Dad’s Mustang was no exception. A few miles outside of Evansville on Highway 41, a teen dance hall was letting out. Cars were spilling out in both directions. We were coming down the far side of the four lane highway. No traffic. A car crossed the median and turned in our direction. I saw it clearly. The left lane was open for them. I was going 70 mph and saw no reason to slow down. The National Safety Council’s Defensive Driving Course was a new initiative. Defensive driving was not yet taught in schools. Common sense was relied on.

The carload of young people turned into my lane instead of the empty one closest to them. I hit the brakes and turned our car away from theirs into a four wheel drift, trying to slow down. It all happened in an instant. We hit at similar angles. They had turned onto the road. I pointed away, trying to avoid them. We slammed into them. Andi and I, in the Mustang, went flying off the road and landed at an angle onto a flat, wide culvert ten feet below the road. We bounced along hard on the ground, but came to a stop without hitting anything else.

Tow trucks came. Ambulances arrived. Dad met us in the Deaconess Hospital ER. Andi’s Mom was right behind him. I was okay physically, but not otherwise. Andi was shaken up and injured. Leaning against me, she had been thrown forward and jammed between my chest and the steering wheel upon impact. Her ribs ached. Knowing I had caused her injury was tough to bear. It could have been worse. We did not go through the windshield.

It also could have been a hell of a lot better. I could have slowed down to avoid the other car completely. We could have stayed in Evansville that evening. Pushing boundaries again, I injured the then love of my life, mangled Dad’s car, and did who-knows-what to the kids in the other car. With premature gray hair and the burden of raising her daughter by herself, Mrs. Taylor appeared to age even more, finding her daughter in the ER that evening. The stress of Andi dating such an irresponsible young man undoubtedly contributed to Andi breaking up with me a month later.

Very late that evening, Dad drove me home in Kim’s Carmen Ghia. He told me how relieved he was that neither Andi nor I had been seriously injured. He also said he was extremely disappointed in me for going to Mt. Carmel, against his expressed wishes. The next day he added, “I’m not sure I should tell you this, but the sheriff who called said you were a hell of a driver to keep the car on four wheels. With the top down, you both likely would have died if the car had rolled.”

I kept a straight face, trying my best to look responsible. What I heard, though, was that Andi could have been killed, and I was a hell of a driver. One foot in a near miss of tragic proportions, and the other in my secret thrill of still having my driving chops.

*****

In the 1960s, our generation began to rebel against our parents’ expectations. Freeing women to chart their own course, however, was not a primary focus of the movement. Andi’s choices were 1) get married, 2) get a job, or 3) continue her education beyond high school to hopefully get a better job.

Finding a guy to marry who could support her and get her out of her mother’s house became priority one. We came apart that fall. One Monday morning at school, Kenny, a nerd’s nerd before the term became popular, told me Andi was dating another guy. She was not in school that day. I hadn’t seen her that weekend because of school commitments. I reacted like any immature kid with abandonment issues. Determined to break up with her before she could break up with me, I spent second period in the back of the auditorium writing her an eight page declaration. In itself, my “letter” would have been enough to push her away from me.

I assumed the worst. It did not occur to me to ask her what was up, what she was feeling. Things may have worked out differently, but I doubt it. Our routine in those days was for me to drive to school, then come home, wake up Dad, and go with him to Wesselman’s cafeteria for his breakfast. No eggs, so call it meal number one for him. Afternoon snack for me.

After school, I stopped by her house. She answered the door. I saw her mother was home, so I threw my bundle of lined school paper at her, yelled something stupid, raced down her front steps, and into Dad’s Mustang.

I burned rubber away from her house, around the corner, and the short block to a stop sign. Coming up to the intersection, I saw only a high concrete wall across the street at the closed Chrysler plant. I wanted to escape the anger and hurt I felt. For a brief moment, I saw the concrete wall as my escape. Just as quickly, I came to my senses, hit the brakes, and stopped at the stop sign.

My next plan of escape was to drive to California and find Mom. In Dad’s car. Without telling him. With thirteen dollars in my pocket. Long before credit cards were common, I headed to Mt. Carmel to borrow forty bucks from Tim. Probably would have gotten me to Kansas City. Tim was not home. Instead, I went to see Ernie Barker in his office. He stopped what he was working on and listened to me blubber about my heartbreak. Then he shared some difficult times in his youth. I left feeling less broken and with an understanding of why Dad considered Ernie his best friend. I drove home. When I got there, Dad said nothing about my being more than two hours late. He said he had eaten Saltine crackers, waiting for me. We went to the cafeteria like nothing had happened...on the surface. I was still in turmoil. Dad kept his thoughts to himself.

Later, I learned three things about that day. 1) Ernie had called Dad after I left. 2) When I gave her a chance, Andi later told me she was sorry to break up with me, but needed a boyfriend with a job and a future. My mind understood, my heart did not. And 3) she said that as I drove away that day, her mother shook her head and said, “What a fool.”

I would have asked Andi to marry me in a heartbeat if not for the specter of unhappy parents in our family and my lack of maturity. I did not know what I needed to learn in life yet, but I knew it was substantial.

*****

School became insufferable. I rarely saw Andi, but my humiliation felt constant. Getting laid was at the forefront of guys’ minds. No surprise there. I studied little, got good enough grades, but had no claim to fame. Kart racing as an elementary school kid was far back in the rearview mirror. Andi, however, was a star, one of the beautiful girls. She had dated before me–Jocks or guys with cars. I was a nobody with no previous girlfriend. I did drive to school, though, because of Dad’s schedule. In short, for those few months, I had dated out of my league. Coming down from that high was crushing.

BELOW: Photo in the Evansville Courier Teen Section during my Junior year. I felt embarrassed to have something in my past publicized. In addition, this “something” was only part my doing. Dad did everything except drive for me. Thankfully, few kids at school mentioned this photo and article. Dad thought it was great. During the photo shoot, he had included a few of the bigger trophies he won as mine.

#

To read my previous posts, sign up for a Substack account (if you haven’t already). It’s

free and only requires your email (no cc). Unsubscribe at any time with one click.

To learn about my other books, click the link below to my author’s website.https://bccowlingbooks.com/